(This blog post is an edited version of a piece I wrote for the Austraiian magazine Royals Monthly.)

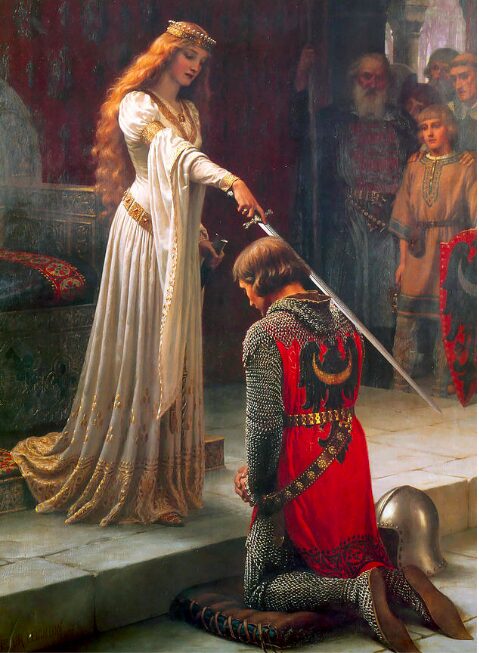

The legend of King Arthur, that great warrior king who united Britain against the Saxon invaders, has captivated people for centuries. The myth speaks to us of something lost – of knights on sacred quests, of chivalric deeds and romance; of magic and mists, dark forests and turreted castles. Little wonder Arthur has inspired so many books, films and poems.

But is any of it true? In his recent bestseller, Unruly, A History of England’s Kings and Queens, David Mitchell writes, ‘He didn’t exist … King Arthur is a lie.’ What a crushing disappointment! Is there really no truth in the legend? Were those tales of Camelot, the Knights of the Round Table and the quest for the Holy Grail simply the product of a medieval monk’s imagination?

Sadly, the case for King Arthur isn’t looking good. One venerable academic remarked, ‘No figure on the borderline of history and mythology has wasted more of the historian’s time.’ Indeed, most historians agree that he never existed.

So where did it all spring from, if not from some ancient truth embellished over time?

Arthur first appeared in Welsh poems of the late 6th and early 7th centuries. They described a hero who united the Britons against the Saxons, which tallies with historical fact – not long after the Romans left Britain, around the middle of the 5th century AD, the Saxons invaded, gradually pushing their way west. The Britons resisted, and by a century later the land was roughly divided between the Anglo-Saxons in the east, and the Britons in the west and in Wales.

Recent discoveries at Tintagel, the Cornish castle strongly associated with King Arthur, suggest that between 450 and 650 AD it was indeed a significant fortress, and at some point likely to have been the seat of a person of high rank who possibly fought the Anglo-Saxons. This period in history is often called the Dark Ages – it was a time of deprivation with a largely illiterate populace. But the Tintagel excavations suggest life here was something different. Archaeologists have discovered comfortable homes, and fragments of glass and pottery from the Mediterranean. It’s all looking rather civilised. Perhaps here existed a wealthy, flourishing community based on trade – Camelot? And did a powerful ruler live here? Intriguingly, a slab of stone dated to the 6th century was found with the word Artognou carved into it. Many Celtic language experts have dismissed this, but others insist the word is a variation of the name Arthur. Have those crusty historians been too quick to dismiss Arthur?

The two most famous early works about Arthur were History of the Kings of Britain (1136) by Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth, and Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur (1485). Both books are generally viewed as a mix of folklore and fiction, but medieval Britain took the story of Arthur to its heart; the people wanted to believe. This tale had everything: flawed characters, impossible quests, moral dilemmas, the ultimate love triangle.

At the end of the 12th century, monks at Glastonbury Abbey in Somerset announced they had discovered the remains of Arthur and his queen, Guinevere. The chronicler Gerald of Wales wrote that there was also ‘… a yellow tress of woman’s hair still retaining its colour and freshness; but when a certain monk snatched it … it straightaway all of it fell into dust.’ We’d love to believe, but it’s now thought (there go those historians again) this discovery was more than likely a fraud dreamt up by the monks as a fundraiser, after fire destroyed a significant proportion of the abbey.

In 1278, King Edward I, a committed believer in Arthur, visited Glastonbury and ordered these remains to be re-exhumed and moved to the abbey’s high altar. Two hundred years later, Henry VII, who, as a Welsh Tudor, claimed ancient descent from Arthur, named his first-born after the legendary king, and in 1486 the young Prince Arthur was christened at Winchester Cathedral (Malory had identified Winchester as the site of Camelot). A replica of the legendary round table, dating from around 1275, remains at Winchester to this day.

Arthur and Guinevere’s bones’ were lost when Glastonbury Abbey was looted during Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. His father, Henry VII, must have been turning in his own grave.

In the 17th century, the Renaissance brought changes in society and culture, and as science began to take over from superstition, the Arthurian legend lost some of its appeal. King Arthur wasn’t entirely dismissed, but he was taken less seriously. Then in the 19th century came the Romantics and the Gothic revival. Medieval romance was back. Wordsworth wrote of the Holy Grail, and in Tennyson’s work Idylls of the King, Sir Lancelot wasted his whole heart for one kiss from Guinevere’s perfect lips.

Today, Arthur isn’t going away. The films and TV series (and books! Give my Queen, King, Ace a whirl!) just keep on coming, and historians and archaeologists remain on his trail, digging to uncover any truth in that myth.

On the cliffs at Tintagel is a sculpture called Gallos (Cornish for ‘power’) (see below). It was installed in 2016, and to many it represents the ethereal nature of the Arthurian legend – the mystery, the gaps in our knowledge. We fill those in with what we’d like to believe, those tales of bravery and chivalry and magic. People stare, and think about what it represents. Was Arthur real? Wouldn’t we all like to believe he was?